by Jacquelyn Thayer

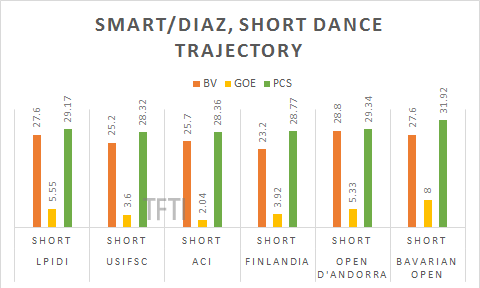

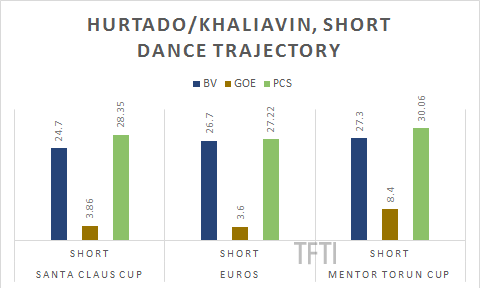

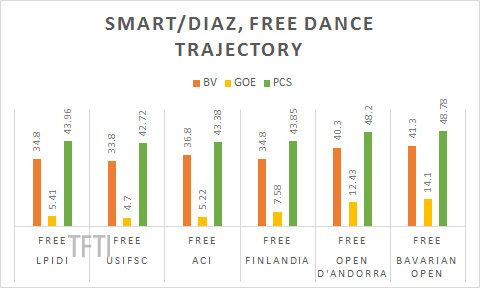

After publishing in August a procedure for selection of the team to represent the nation in ice dance at the 2017 World Championships — giving the slot to the team with the highest short dance technical score at an international event — the Spanish winter sports federation yesterday courted controversy by declaring that ice dancers Olivia Smart and Adrià Díaz, who finished second at the national championships (for which, alas, official, detailed results are not available) and whose highest international short dance technical score was lower than that of national champions Sara Hurtado and Kirill Khaliavin, would be attending the World Championships. They outlined their change of heart with reference to numbers. TFTI, too, enjoys numbers.

Some supplemental information regarding the above data:

1. Euros was the only ISU championship included here, and by those standards — including the most difficult field of any of the above events — could be reasonably argued to have somewhat more conservative scoring than that proffered at B and Challenger Series competitions.

2. Smart and Díaz’s first competition came in July, and the next three in September and October; Hurtado and Khaliavin were unable to compete internationally until December due to his recent prior representation of Russia.

3. US International Figure Skating Classic, Autumn Classic International and Finlandia Trophy are Challenger Series events. All others listed above, bar Euros, are Senior Bs, which traditionally feature smaller judging panels by 2-4 members than championships or Grand Prix events, less competitive rosters, and far more generous technical scoring; it’s no coincidence that many lower-ranked skaters pick up TES entry minimums for the ISU championships at such events and fail to replicate them at those championships, and that scores at these events are not considered for ISU personal or season’s bests.

4. Smart and Díaz’s total Grade of Execution (GOE) score of 22.1 at Bavarian Open, a 25% increase over their previous, pre-Nationals outlier, is higher than that obtained by past top six-ranked World competitors Kaitlyn Weaver and Andrew Poje, Madison Hubbell and Zach Donohue, and Piper Gilles and Paul Poirier at Four Continents (an ISU championship event) the same week, and 0.65 lower than that of Four Continents bronze medalists Madison Chock and Evan Bates. Their total score including non-technical marks, however, was 9-15 points lower than those of Chock and Bates, Weaver and Poje, and Hubbell and Donohue.

5. In a sport that deals in decimals, a tie has only been addressed in the very rare cases in which two skaters have received identical scores (an unusual outcome given the many factors that comprise a single score); there is no recognized +/- 0.1 margin of error, as the federation suggests in this communication. At the European Championships discussed here, the difference between ice dance silver and bronze was 0.08 points; at the 2014 World Championships, 0.06 separated the gold and bronze medalists in dance.

6. With a berth for Spain in ice dance at the 2018 Olympics at stake, Spain’s single entry in ice dance must ideally finish relatively well at this World Championships; only 24 teams will compete in Pyeongchang, and 19 country slots will be determined at Worlds. At least five countries at Worlds are almost certain to qualify two or three entries based on strong results from their competitors, with other countries then filling out the remaining spots in order of finish (from there, an additional five countries — bringing the entry total to that 24 — may also qualify spots at a designated early international event in the upcoming season; this year, as in the past, it will be Challenger event Nebelhorn Trophy). To finish well at Worlds, Spain’s couple must also qualify within the top 20 teams after the short dance in order to compete the full event.

Per current season’s best total scores — those scores obtained at a Challenger Series event, Grand Prix, or ISU championship — when considered among teams currently likely to compete at Worlds, Hurtado and Khaliavin’s best score of 141.36, obtained at Euros, would rank them 27th. However, Smart and Díaz’s of 142.12, achieved at Finlandia Trophy, only places them 25th. In the short dance, the same standings hold with even closer scores: Hurtado/Khaliavin earned 56.52 at Euros, Smart/Díaz 57.12 at the U.S. Classic. In a comparison of so many events, it’s highly probable that some teams ranked ahead will falter here, but teams currently ranked below the Spanish couples may also surge. Essentially, there’s little in terms of ISU data, rather than that offered by Senior B scoring, to be considered terribly predictive for Worlds and pre-Olympic strategy.

7. Marta Olozagarre, one of two ISU officials who signed off on this formal decision, was on the judging panel for senior ice dance at US Classic, Autumn Classic, Open d’Andorra and Euros — four of nine events here, and half of Smart/Díaz’s. This is not to suggest any misdoing (indeed, Olozagarre has not been a consistently high scoring judge for the Spanish couples), but simply to highlight the close ties between the idea of that single judge who could impact a GOE mark (see below), and the nature of officials involved in deciding the fate of those dance teams in question.

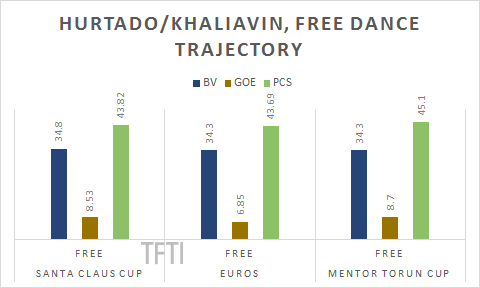

Additionally, an argument relying on the premise of “if/then,” as the Spanish federation’s does in arguing that two different technical scores are really a tie, is fundamentally flawed. If, for example, a team had ended up falling at a given event where they actually skated cleanly, then their score would have ended up lower than it was, and vice versa. If a random judge loved one type of lift and felt another tended to look sloppy, perhaps, just perhaps, they’d let that subjectivity impact their assessment of GOE. These are only examples, but the underlying point is that “if/then” is a poor criteria for revising a 6-month-old ruling under which three senior ice dance teams had approached their season. It’s an especially questionable argument given the larger GOE trajectories of these two couples.

Furthermore, an argument asserting that already-allotted GOE is so unfixed as to be worth speculating upon undermines any premise of accuracy in ice dance judging. Grades of Execution are meant to be determined by specifically outlined, if vague, criteria; this claim, however, suggests that both team’s short dance marks were open to subjective fudging. But that revelation, perhaps, is the best gift this decision could have provided the sport’s audience.