In this PCS series as in all analytical articles, it has generally been TFTI’s aim to provide some deeper insight into the numbers presented — related or not to on-ice performance. But in the matter of Grades of Execution in this first half of the 2015-16 season, our mission may have failed.

It should first, though, be remembered that GOEs of +/-1, 2 or 3 are not mathematically equivalent to 1, 2 and 3. For all non-step sequence dance elements (including choreographic elements), pattern dance elements and Level 1 footwork:

+1 = 0.6

+2 = 1.2

+3 = 1.8

Negative marks for non-step elements work on a sliding scale (for choreographic elements, all negative GOE equates to -0.1):

-1 = -0.3 (Level 1 only); -0.5 (Levels 2-4, Level 1 footwork, all pattern elements)

-2 = -0.7 (Level 1 only); -1.0 (Levels 2-4, Level 1 footwork, all pattern elements)

-3 = -1.0 (Level 1 only); -1.5 (Levels 2-4, Level 1 footwork, all pattern elements)

For choreographed step sequences, the arguable heart of today’s ice dance, GOE has dramatically greater effect at Level 2 and above:

+1 = 1.1 / -1 = -1.0

+2 = 2.2 / -2 = -2.0

+3 = 3.3 / -3 = -3.0

For further reference, the 2015-16 Scale of Values is available in Communication 1936, while Communication 1937 provides guidelines intended to identify how Grades of Execution should be assigned.

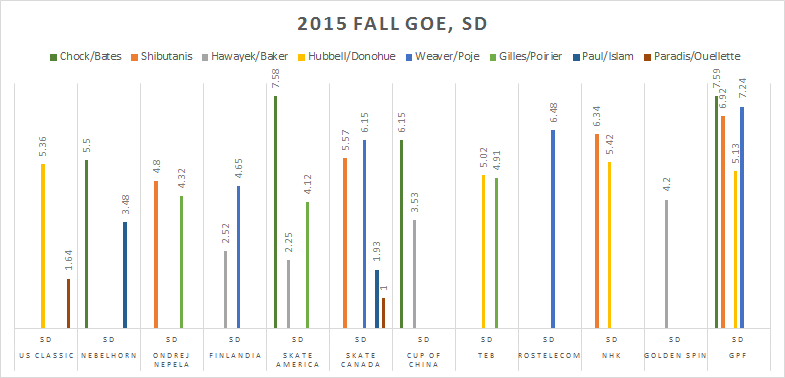

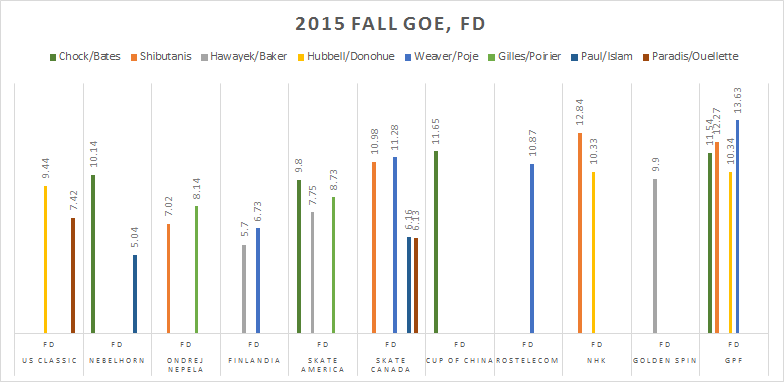

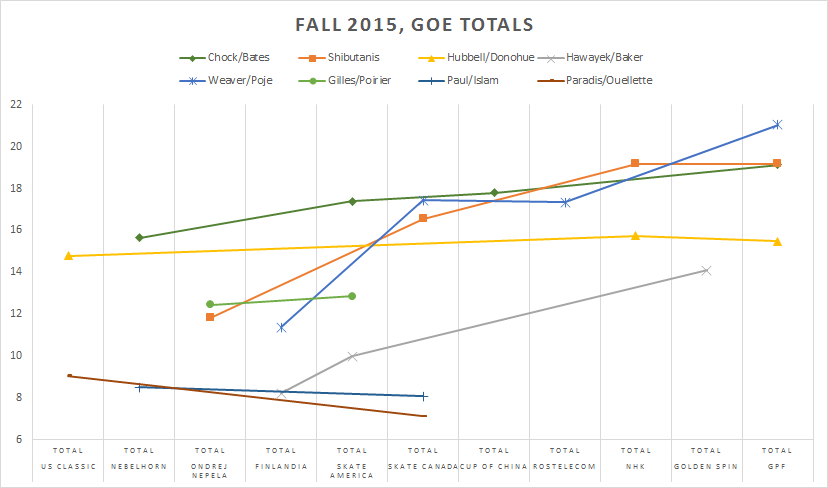

A rather strange autumn that included a tragically abbreviated Trophee Eric Bompard, along with pre- or mid-event withdrawals for other skaters, means that data is rather less thorough than would be ideal for a typical mid-season evaluation. However, every major U.S. and Canadian dance team has competed at least two full events, and this provides at least a fair opportunity to tabulate total GOE, by the segment, at each:

The columns do little to tell a full story.

Kaitlin Hawayek and Jean-Luc Baker’s Finlandia Trophy free dance makes the lower end of the spectrum, fair for a skate in which an entire element — their straight line lift — was lost, thus eliminating one GOE category (though also eliminating the risk of negative GOE for that one element). Their subsequent Skate America skate was considerably smoother, reflected in a GOE improvement of +2.05. Alexandra Paul and Mitch Islam’s Nebelhorn free dance included a shaky straight line lift, hitting Level 4 requirements but correctly penalized by -1.10 in GOE. Restoring that lost mark to a neutral 0 would bring the team to a GOE total of 6.14, almost identical to that assigned over a month later at Skate Canada — where they actually received only positive GOEs, all greater than 0. But with lower footwork levels in the second event came, too, a halving of GOE on those elements, despite a neater overall performance than in the program’s debut; with step GOE affected in part by partner distance and types of hold, any possible choreographic pitfalls present at the second outing were equally apparent at the first. Similarly, a short dance GOE loss of 1.55 from Nebelhorn to Skate Canada is not easily supported by any specific comparisons between skates.

Individual element GOEs can also generate some discussion. One controversial case came in the Grand Prix Final free dance for Madison Chock and Evan Bates, with twizzles that included a significant stumble receiving a +2 mark from one judge, for a final positive GOE of 0.01 — inappropriate to be sure, but still sufficient, in the event field, to drop the team to last place on that element’s scoring (fifth-qualified Final entrants Madison Hubbell and Zach Donohue, the third-ranked U.S. couple, actually achieved the season’s highest twizzle GOE, 1.71, at that same event — an example of GOE in its democratic usage). But more extravagantly questionable marks on the same element have appeared in the recent era, such as a +1.11 for this world championship set despite significant synchronization issues — interestingly, the same GOE assigned to this sharper set from tenth-place Hubbell and Donohue at the same event.

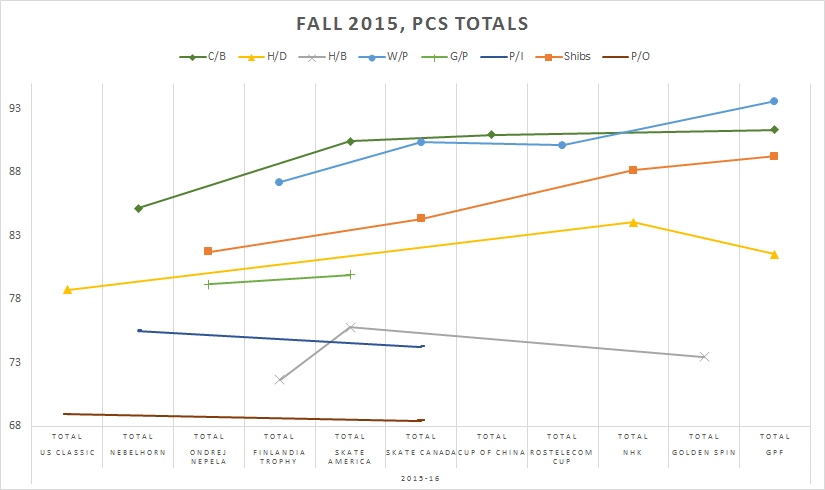

While GOE is assigned by the same judging panel responsible for component marks, a chart of totals in each category shows little consistent relationship between the scores. Though a performance characterized by visible element error should be expected to lower an event’s GOE total — and it’s clear the GOE graph is the more erratic of the two — PCS should also be negatively impacted to some respect. But we have, of course, discovered that this idea is seldom applied so logically.

The impending U.S. and Canadian championships will offer an interesting testing ground. Where PCS traditionally skyrockets, can the still more practically-applied GOE take a similar path — and may similar questions arise within ranks?

Next up, a look at PCS among North America’s rising pairs.