by Jacquelyn Thayer

Editor’s Note: This article has been sourced through both public documents and interviews obtained as possible. For the sake of both accuracy and education, we welcome more detailed information on U.S. funding and will gladly update if and when that information is made available.

Two for the Ice took its first look at athlete funding with the matter of prize money — funds distributed to skaters who rank highly at the ISU’s plum international events, from the Grand Prix to the championships. Now we’ll consider the more foundational base of institutional support — those funds provided by North America’s major national sporting bodies to ease the quite considerable burden of day-to-day training costs. That the sport’s own institutions provide financial support to athletes at many levels of achievement and age is an obvious boon but, like prize money, it can only stretch so far and so wide.

For Canadian athletes in amateur Olympic sport, institutional funding derives first from Sport Canada’s Athlete Assistance Program, which provides annual sums, in a series of installments, for top-achieving athletes nominated by their federation for support. Happily for these athletes, Sport Canada recently announced plans to increase funding heading into this Pyeongchang sporting season — but for now, we’ll work with the data from the 2016-17 season.

Number of senior athletes funded by season’s end compared with total number of senior competitors across January’s Canadian Figure Skating Championships. Note: top-funded pair Julianne Séguin and Charlie Bilodeau did not compete at Canadians.

This financial support can be distributed, at the highest senior funding level, to a maximum of 30 athletes per sport — a capped total of $540,000 CAD. Support for athletes, however, is actually offered in tiered levels. In its 2016-17 Carding Criteria announcement, Skate Canada defined the tiers in terms of specific goalposts (which remain valid for 2017-18’s funding):

* Those routinely attaining the highest results receive $18,000 under one of two classifications: Senior International (SR-1 or SR-2) carding, for those on the World Championship stage, or Senior National carding (SR), reserved for otherwise strong candidates who may have fallen out of the top half of Worlds finishers, have dealt with injury or pregnancy in the previous season, or are World or Olympic medalists returning from a hiatus. SR candidates must finish top three at Nationals, compete at the World Championships, or achieve an international season’s best that’s 80% of the World Win Target — more on that below. Twenty-two skaters at the outset of the 2016-17 season met this criteria, 20 by year’s end.

* Up-and-coming senior competitors may also be funded as C1 cardholders, candidates who have met the Senior National criteria for the first time in their career. While the actual amount of funding matches that provided to SR, SR-1 or SR-2 cardholders, it’s classified as a higher tier of Development carding. While Elisabeth Paradis and François-Xavier Ouellette were nominated at this carding level, their pre-season retirement subsequently left the category unfilled.

* Development carding (DEV) is the introductory level of funding — $10,800 offered to juniors who competed on the JGP and/or World Junior Championships and to rising seniors who have competed on the Grand Prix or at a senior international recognized by Skate Canada. The season’s best international score for these skaters must be 60% of the World Win Target. Generally, skaters who have attained Senior-level funding — or who have held a Development card for four consecutive or non-consecutive seasons — are not, or are no longer, eligible for Development funding, though exceptions may be made for experienced skaters competing in new partnerships. Up to 14 skaters by fall 2016 were nominated at this level, including in a partial sum of $3,600 for junior Justine Brasseur. At the end of the season, 12 DEV recipients remained standing, with funding on hold for teams who split mid-season.

Athletes receive this year-long support in twice-monthly installments — a total of $1,500 a month for the top earners, $900 for those at the secondary level. Those who retire, or otherwise choose to cease their funding before the cycle’s conclusion, are removed from the carding list, with the next athlete(s) up benefiting.

So that World Win Target? This goalpost refers to the rounded average total of the top two finishers in a given discipline at that preceding season’s World Championships. In ice dance, this set a high bar given the record-breaking scores doled out at 2016’s event; between the totals for Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron and Maia and Alex Shibutani, the averaged 2016-17 World Win Target for Canadian ice dance carding candidates was 191.

The 80% criteria required for SR nominees was itself a fairly steep 153, a threshold that would be met by a total of 28 teams on the ISU’s season’s best list for 2016-17 and by only 19 teams in 2015-16 — though this excludes results from non-Challenger Senior B events, an exception that Skate Canada does seem to allow.

Heading into 2016-17, no ice dance team not already eligible in the past for Senior International or Senior National status met this standard. This was further underscored by an initial SR carding status for former Worlds competitors and national medalists Alexandra Paul and Mitch Islam: despite a fourth-place finish at 2016’s Nationals, and no assignment to that year’s Worlds, the Injury clause was successfully invoked given both legitimate challenges to their 2015-16 season and the credentials in Canada’s ice dance field to justify continued high-level carding.

As relative newcomers to the Sport Canada system, Paradis and Ouellette, who did make the 2016 national podium and competed in the short dance at that year’s Worlds, were, as noted above, initially assigned C1 status before announcing their split at season’s start. But with Paradis and Ouellette’s early removal from the envelope ranks, the senior dancer next in line, Shane Firus — who had met carding nomination criteria with previous partner Lauren Collins and was already matched in a new partnership with Carolane Soucisse, a rare situation given a spate of retirements in Canadian senior ice dance in 2016 — moved up to receive Development carding. Similarly, Paul and Islam’s own mid-season retirement in December, along with that of fellow ice dancer Mackenzie Bent, benefited next-in-line skaters for the remaining duration of the year’s carding cycle.

But the score threshold situation has become stickier still heading into 2017-18, with only the top three Canadian ice dance teams having exceeded the 80% goal (157.60) of the 2017 World Win Target average of 197 — with the highest mark at that event set, actually, by Canada’s own Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir. Before their departure from competition, Paul and Islam picked up 144.85 on the Grand Prix, while Soucisse and Firus, fourth at this season’s Nationals, have an official season’s best of just 128.78, obtained at Autumn Classic International, and an unofficial international best of 130.64 from Senior B event Cup of Nice.

Soucisse and Firus do meet the 60% threshold criteria (118.20) necessary for 2017-18 Development carding, and neither has yet maxed out four seasons at that level. Junior national champions Marjorie Lajoie and Zachary Lagha are also in good stead, having scored 148.26 at the World Junior Championships, as should be fellow juniors Alicia Fabbri and Claudio Pietrantonio (127.89 on the Junior Grand Prix) and junior national silver medalists Ashlynne Stairs and Lee Royer (124.14, Junior Grand Prix). But 2017-18 senior national team members Haley Sales and Nikolas Wamsteeker scored only 112.52 at their only major international, Autumn Classic, and no other senior dance team set to compete in the coming year has attended a Grand Prix, Challenger event, or major Senior B.

This analysis, of course, doesn’t even touch on the Canadian pairs — but Canadian pairs are also in far stronger shape, with season’s bests for the top four teams ranking within the top 14 overall, while fifth- and sixth-place national finishers Brittany Jones and Joshua Reagan (SB 155.48) and Camille Ruest and Drew Wolfe (SB 167.19) more than clear the 60% World Win Target bar.1 However, at least through 2016-17, one team member has faced a different conundrum: Sport Canada-derived funding is available only to Canadian citizens or those on track to citizenship, a snag that affected American-born Piper Gilles until the 2014-15 season and had thus far impacted Russian-born Lubov Iliushechkina. Last season’s carding list stated that funding was pending permanent resident status, a carding situation that remained unchanged over the course of the 2016-17 season. For 2017-18, Iliushechkina has been nominated without a similar disclaimer — according to a preliminary carding list that has since been removed from Skate Canada’s website — but final status remains to be confirmed.

Via their High Performance Grant, Skate Canada does offer an alternative for top five finishers who do not meet Sport Canada’s multitude of criteria. Funds offered vary with placement, but are consistent across disciplines. By these rates, a senior silver medalist like Iliushechkina could then be eligible for a solid $12,000, though for fourth- and fifth-place finishers, the funding ratio is less favorable when compared with Development card support.

In addition to the High Performance Grant, Skate Canada itself provides a few additional incentives to its top-performing athletes. The High Performance Athlete Assistance Grant benefits international-level competitors who do not receive funds from Own the Podium, Canada’s formal joint Olympic funding initiative2, at rates, per High Performance Director Mike Slipchuk, in the range of roughly $1,000-$1,500 per year for up to 25 athletes over the past two seasons; athletes receive equal funding apiece from that allotted share of the budget. A range of smaller travel grant and scholarship stipends are also on offer.

As a final caution for those keeping an eye on next season’s carding offers, it’s worth noting that in its breadth of potential recipients, 2016-17’s first draft list bore little resemblance to the subsequent versions — and few solid conclusions, aside from the occasional hint of retirement or split, can usually be drawn from a preliminary list.

Team USA athletes — across all Olympic sports — do not receive government funding. However, the non-profit federation bodies for those sports, including the U.S. Figure Skating Association, do provide support to a number of athletes through multiple means, including scholarship and grant programs.

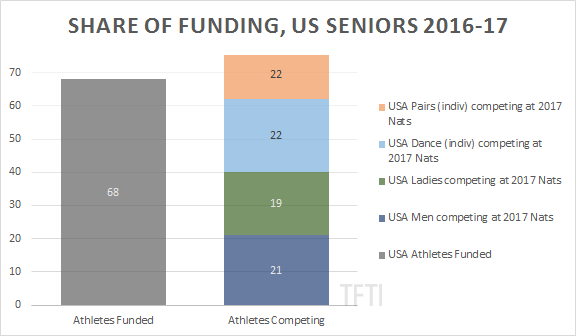

Number of senior envelope recipients competing in 2016-17 compared with total number of senior competitors across January’s U.S. Figure Skating Championships.

Athletes who did not compete at any point in the season are excluded from this funding total.

Athletes who competed one segment at the national championships are included among competitors.

U.S. Figure Skating’s Team Envelope program, targeting national medalists and international competitors at senior, junior and, in two cases, novice levels3, suggests the best corollary to Sport Canada and Skate Canada’s funding procedure. At time of publication, U.S. Figure Skating had not responded to requests from Two for the Ice for specific information regarding the range of funds distributed through this program, or the percentage of its overall athlete funding allotted via team envelopes. However, according to U.S. Figure Skating’s tax disclosure for fiscal year 2015-16, $3,755,712 was allocated for the organization’s “Athlete Program” under Part IX’s Statement of Functional Expenses, a broad pool of expenditures that includes far more than basic funding allocations. So more specifically, according to their most recent fact sheet, “[t]hroughout the 2016-17 season, U.S. Figure Skating will directly distribute more than $1 million to its athletes through training grants and financial assistance.” While this number includes non-envelope funding like the $145,000 distributed via the federation’s national podium bonus program — a form of incentive not available to Canadian medalists — and the U.S. Figure Skating Memorial Fund4, it is also nearly double the maximum allotted to skaters through Sport Canada’s program. But it’s also necessary to break down the available data.

In 2016-17, 107 individual athletes ranging from senior champs to 2016’s national novice medalists — and not including the six synchronized skating teams also supported by the program — comprised the four Team Envelope tiers of A (16 skaters), B (20), C (44) and D (27), which are themselves divided into two tiers apiece based on stated criteria. This number included 17 pairs and 17 dance teams. Distribution patterns vary by envelope tier; funding, for example, is delivered four times per season cycle for Team A and B and in bookend installments — September and March — for Team C.

U.S. Figure Skating indicates too that “[in] 2016, nearly 150 skaters” received support via the Memorial Fund; a similar number probably benefited in the 2016-17 season as well, though this number will have included skaters at assorted competition levels and outside the topmost achievement ranks we’re considering here. However, this funding sum is generally larger than that offered via Skate Canada’s Athlete Assistance Grant program, with beneficiaries receiving approximately $2500 in a season.

Assuming that funds allocated to skaters in the 2016-17 season were closer to $1 million than $1.5 million, subtracting allotments for the bonus program and Memorial Fund yields us roughly $500,000 — which, when distributed among a much wider field of athletes than Skate Canada’s carded roster, generally means smaller shares per tier and skater, with $4,000 the median allotment for 2016-17 recipients.

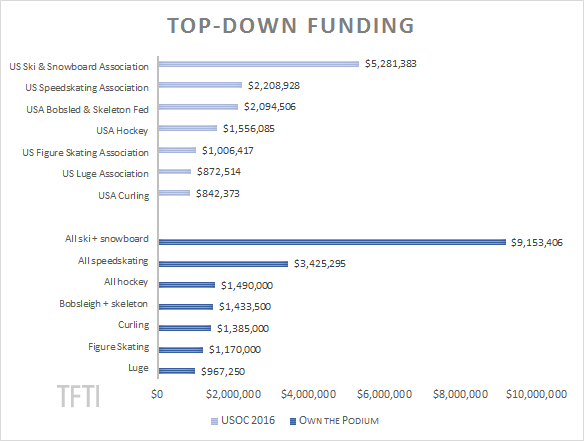

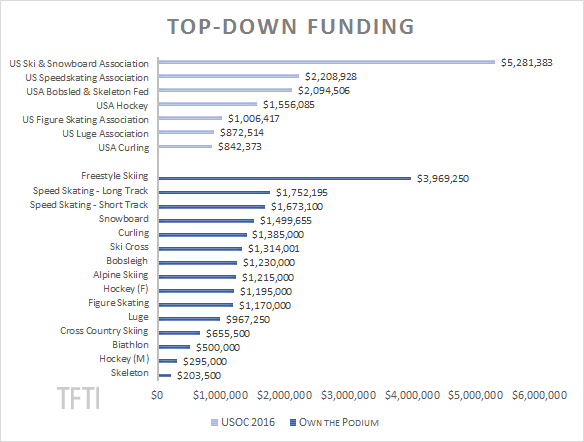

The U.S. Olympic Committee is another source of support, though, like Own the Podium, it tends more towards broad-based measures, such as funding for Olympic Training Centers and support to the individual sport federations; direct funding to athletes is a more targeted practice, disseminated across myriad sports. Per the USOC’s most recent tax disclosure , they provided $1,006,417 in grants and assistance to the U.S. Figure Skating Association in 2016. Team USA’s Operation Gold, “awarding top place finishes” across Olympic sports, provided $6,755,180 to 463 athletes, with plans to significantly increase reward payments per U.S. athlete as of the Pyeongchang Olympics. Assuming consistent payment across sports, this document from U.S. Speedskating provides a look at current World Championship-level funding; in 2016-17, eight U.S. figure skaters would have qualified, with Maia and Alex Shibutani picking up a Team USA-best $4,000 each as ice dance bronze medalists.

Comparison of funding by winter sport from the U.S. Olympic Committee and Canada’s Own the Podium program. Chart one consolidates Canada’s sports to better align with the format of U.S. Olympic federations for ease of comparison. At time of publication, $1 CAD = $0.78 USD.

While a lack of transparency in some respects curtails public understanding of just how much institutional support is on offer for North America’s figure skaters, one theme that is obvious is one little different from that which underlies prize money: success breeds funding which, ideally, breeds more success. As a business model, it’s not unsound. As a model for an expensive sport’s growth, it’s more complex. In cases like that of the U.S., where support comes not through government stipends but from charitable donation and corporate partnership, the pursuit of consistent and expansive funding is a job in itself, but Canada’s system, too, presents necessary caps: sport is not as popular a government budgetary category as it is in a nation like Russia, where elite Olympic athletes may be granted cars and housing in addition to regular cost coverage. For those athletes reliant only on Skate Canada’s own contributions, the situation again comes down to a federation’s own means.

There are trade-offs, and athletes competing for Canada and the U.S. may arguably have more leeway than others in terms of career choice — coaching decisions, choreographer selection, and training base. But while federations which hold fewer purse strings may also have less leverage, simple economics can, in the end, help dictate those very same choices.

- The 2017-18 World Win Target for pairs is 231.

- Own the Podium allotted $1,170,000 for figure skating in 2016-17, funds which include support for coaches and initiatives in addition to support for individual, world medal-contending athletes.

- Sophia and Christopher Elder and Maxim Naumov; other skaters have advanced to junior or senior after earning envelope status as novice competitors.

- A sum averaging $350,000 annually through the Competitive Skaters Assistance Program and Academic Scholarship Program, plus a total $4,000 allotted through the RISE Youth Essay Contest.